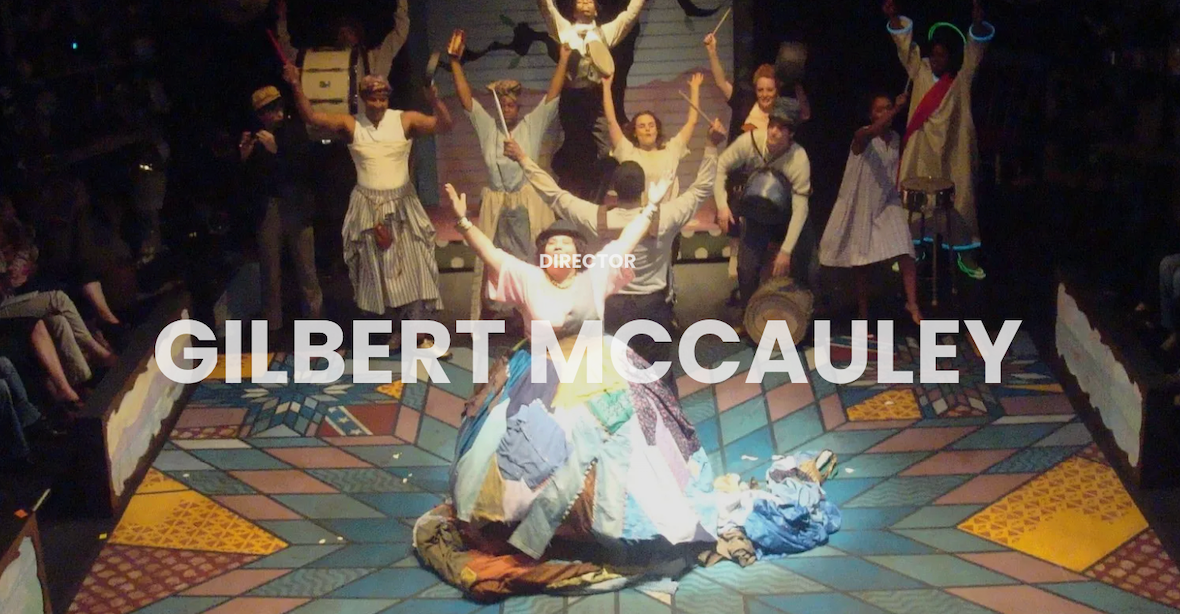

Why movement may beat words at speed: dance as a first language

The idea in one sentence

Because the brain can pick up on movement faster than it processes words or tone, dance can deliver core intent to an audience faster than words.

Your brain reads bodies fast

Words ask the brain to decode symbols, assemble grammar, and map meaning. Bodies skip that line. A lifted chest, a collapse to the floor, a reach across space. You read it in an instant. Dance can turn that native fluency into art and, at times, into the quickest channel we have.

The brain can detect human movement very quickly. Some studies show responses to biological motion in about 100 to 150 milliseconds. This does not mean full comprehension happens instantly, but it does show that the brain is tuned to notice motion almost right away. By comparison, language markers appear later. Word meaning often shows up in brain activity around 400 milliseconds. Emotional tone in speech can take 500 to 1000 milliseconds to register, although some cues may be recognized sooner in certain contexts.

Movement carries emotion with precision

People can understand emotion and intention from movement without hearing a single word. Even when the body is reduced to a set of dots in point-light displays, observers can still identify actions and feelings. Silent film clips also provide enough information for people to interpret mood or intent.

Thin slices, swift calls

People form accurate judgments from very short clips of behavior. That “thin-slice” effect supports the everyday sense that a few seconds of movement can signal warmth, dominance, confidence, or strain before a single sentence lands.

More simply...with dance, there is no need to obsess if your text was misinterpreted, because the visual is more straightforward.

Why this matters for dance

- Clarity under noise. Music can drown speech, but bodies still speak. Visual motion keeps a clean channel when audio fails. Evidence from multimodal studies shows that visual cues can speed neural uptake of auditory content, which hints at a head start for movement in tough settings.

- Cross-language access. Movement bypasses vocabulary limits. An audience does not need shared words to grasp reach, recoil, or resolve.

- Speed plus nuance. Early neural responses do not equal crude signals. The brain can flag human motion fast and still encode complex social meaning within the next few hundred milliseconds. Recent work on observed touch shows affective meaning as early as 150 milliseconds.

How the Brain Helps

The mirror system in the brain provides part of the explanation. When a person watches movement, parts of their motor system activate as if preparing to make the same motion. This response helps people recognize intention quickly. It also explains why movement feels like a universal channel of communication.

Why It Matters for Dance

Language allows precision, but movement often carries meaning faster. A gesture can comfort, warn, or inspire with no words attached. For dancers and choreographers, this understanding confirms what practice already shows. Movement reaches audiences directly and powerfully.

Practical takeaways for makers and teachers

Lead with shape. Open a piece with a clear, readable motif. A rise, a pull, a cut to stillness. Your audience locks in before any text or narration would land.

Design contrast. Sharp to fluid. Bound to free. The visual system flags distinct kinematic cues quickly, which boosts recognition and emotional read.

Trust silence. When the story peaks, let the body carry the line. Studies show accurate affect judgments from movement alone.

Choreograph attention. Big group unisons can set the scene; a single mover can punctuate meaning. Early motor and visual responses support both global and local cues.

Recent Posts